In 2016, I gave up Diet Coke. This was no small adjustment. I was born and raised in suburban Atlanta, home to the Coca-Cola Company’s global headquarters, and I had never lived in a home without Diet Coke stocked in the refrigerator at all times. Every morning in high school, I’d slam one with breakfast, and then I’d make sure to shove some quarters (a simpler time) in my back pocket to use in the school’s vending machines. When I moved into my freshman college dorm, the first thing I did was stock my mini fridge with cans. A few years later, my then-boyfriend swathed two 12-packs in wrapping paper and put them under his Christmas tree. It was a joke, but it wasn’t.

You’d think quitting would have been agonizing. To my surprise, it was easy. For years, I’d heard anecdotes about people who forsook diet drinks and felt their health improve seemingly overnight—better sleep, better skin, better energy. I’d also heard whispers about the larger suspected dangers of fake sweeteners. Yet I’d loved my DCs too much to be swayed. Then I tried my first can of unsweetened seltzer at a friend’s apartment. After years of turning my nose up at the thought of LaCroix, I realized that much of what I enjoyed about Diet Coke was its frigidity and fizz. That was enough. I switched to seltzer on the spot, prepared to join the smug converted and receive whatever health benefits were sure to accrue to me for my good behavior.

Except they never came. Seven years later, I feel no better than I ever did drinking four or five cans of the stuff a day. I still stick to seltzer anyway—because, you know, who knows?—and I’ve mostly forgotten that Diet Coke exists. But the diet sodas had not, as it turns out, been preventing me from getting great sleep or calming my rosacea or feeling, I don’t know, zesty. Besides the caffeine, they appeared to make no difference in how good or bad I felt at all.

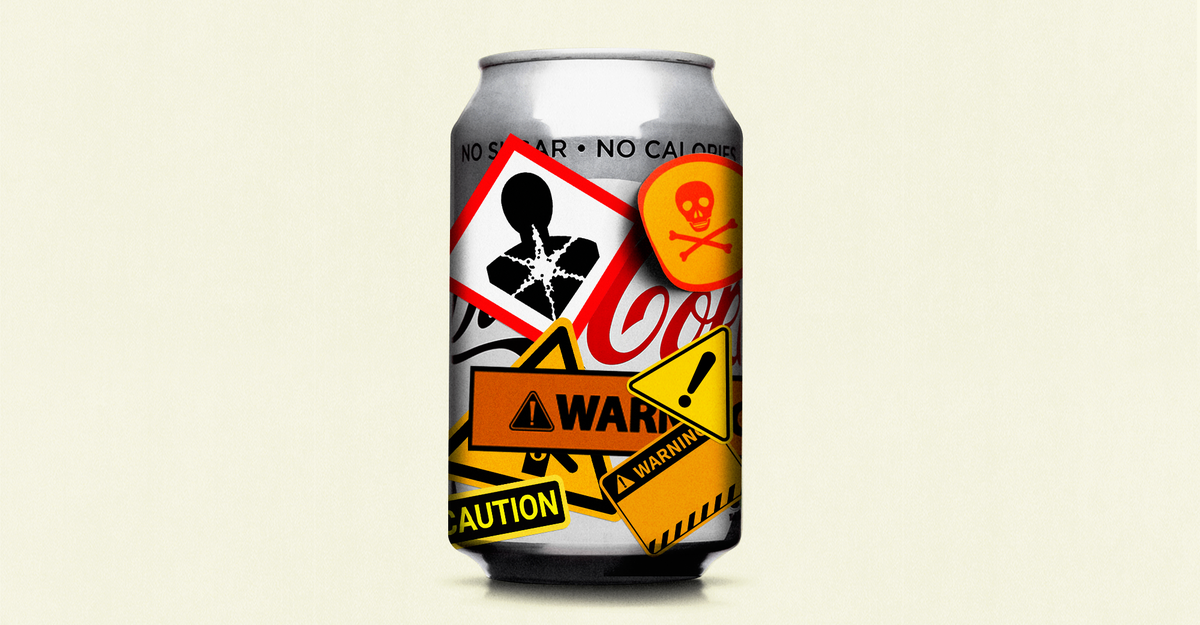

Yesterday, Reuters reported that the WHO’s International Agency for Research on Cancer will soon declare aspartame, the sweetener used in Diet Coke and many other no-calorie sodas, as “possibly carcinogenic to humans.” I probably should have felt vindicated. I may not feel better now, but many years down the road (knock on wood), I’ll be better off. I’d bet on the right horse! Instead, I felt nothing so much as irritation. Over the past few decades, a growing number of foods and behaviors have become the regular subject of vague, ever-changing health warnings—fake sweeteners, real sugar, wine, butter, milk (dairy and non), carbohydrates, coffee, fat, chocolate, eggs, meat, veganism, vegetarianism, weightlifting, drinking a lot of water, and scores of others. The more warnings there are, the less actionable any particular one of them feels. What, exactly, is anyone supposed to do with any of this information, except feel bad about the things they enjoy?

It’s worth reviewing what is actually known or suspected about diet sodas and health. The lion’s share of research on this topic happens in what are known as observational studies—scientists track consumption and record health outcomes, looking for commonalities and trends linking behavior and effects. These studies can’t tell you if the behavior caused the outcome, but they can establish an association that’s worth investigating further. Regular, sustained diet-soda consumption has been linked to weight gain, Type 2 diabetes, and increased risk of stroke, among other things—understandably troublesome correlations for people worried about their health. But there’s a huge complicating factor in understanding what that means: For decades, advertisements recommended that people who were already worried about—or already had—some of those same health concerns substitute diet drinks for those with real sugar, and many such people still make those substitutions in order to adhere to low-carb diets or even out their blood sugar. As a result, little evidence suggests that diet soda is solely responsible for any of those issues—health is a highly complicated, multifactorial phenomenon in almost every aspect—but many experts still recommend limiting your consumption of diet soda as a reasonable precaution.

A representative for the IARC would neither confirm nor deny the nature of the WHO’s pending announcement on aspartame, which will be released on July 14. For the sake of argument, let’s assume that Reuters’s reporting is correct: In two weeks, the organization will update the sweetener’s designation to indicate that it’s “possibly carcinogenic.” To regular people, those words—especially in the context of a health organization’s public bulletins—would seem to imply significant suspicion of real danger. The evidence may not yet all be in place, but surely there’s enough reason to believe that the threat is real, that there’s cause to spook the general public.

Except, as my colleague Ed Yong wrote in 2015, when the IARC made a similar announcement about the carcinogenic potential of meat, that’s not what the classification means at all. The IARC chops risk up into four categories: carcinogenic (Group 1), probably carcinogenic (Group 2A), possibly carcinogenic (Group 2B), and unclassified (Group 3). Those categories do one very specific thing: They describe how definitive the agency believes the evidence is for any level of increased risk, even a very tiny one. The category in which aspartame may soon find itself, 2B, makes no grand claims about carcinogenicity. “In practice, 2B becomes a giant dumping ground for all the risk factors that IARC has considered, and could neither confirm nor fully discount as carcinogens. Which is to say: most things,” Yong wrote. “It’s a bloated category, essentially one big epidemiological shruggie.”

The categories are not at all intended to communicate the degree of the risk involved—just how sure or unsure the organization is that there’s a risk associated with a thing or substance at all. And association can mean a lot of things. Hypothetically, regular consumption of food that may quadruple your risk of a highly deadly cancer would fall in the same category as something that may increase your risk of a cancer with a 95 percent survival rate by just a few percentage points, as long as the IARC felt similarly confident in the evidence for both of those effects.

These designations about carcinogenicity are just one example of how health information can arrive to the general public in ways that are functionally useless, even if well intentioned. Earlier this year, the WHO advised against all use of artificial sweeteners. At first, that might sound dire. But the actual substance of the warning was about the limited evidence that those sweeteners aid in weight loss, not any new evidence about their unique ability to harm your health in some way. (The warning did nod to the links between long-term use of artificial sweeteners and increased risks of cardiovascular disease, Type 2 diabetes, and premature death, but as the WHO noted at the time, these are understood as murky correlations, not part of an alarming breakthrough discovery.)

The same release quotes the WHO’s director for nutrition and food safety advising that, for long-term weight control, people need to find ways beyond artificial sweeteners to reduce their consumption of real sugar—in essence, it’s not a health alert about any particular chemical, but about dessert as a concept. How much of any sweetener would you need to cut out of your diet in order to limit any risks it may pose? The release, on its own, doesn’t specify. Consider a birthday crudités platter instead of a cake, just to be sure. (Is that celery non-GMO? Organic? Just checking.)

The media, surely, deserve our fair share of blame for how quickly and how far these oversimplified ideas spread. Many people are very worried about the food they eat—perhaps because they have received so many conflicting indicators over the years about how that food affects their bodies—and flock to news that something has been deemed beneficial or dangerous. At best, the research that many such stories cite is rarely definitive, and at worst, it’s so poorly designed or otherwise flawed that it’s flatly incapable of producing useful information.

Taken in aggregate, this morass of poor communication and confusing information has the very real potential to exhaust people’s ability to identify and respond to actual risk, or to confuse them into nihilism. The solution-free finger-wagging, so often about the exact things that many people experience as the little joys in everyday life, doesn’t help. When everything is an ambiguously urgent health risk, it very quickly begins to feel like nothing is. I still drink a few Diet Cokes a year, and I maintain that there’s no better beverage to pair with pizza. We’re all going to die someday.