The Big Picture

- John Ford’s film The Iron Horse revitalized the Western genre in 1924, setting the mold for future Westerns to come.

- The film showcases Ford’s admiration for grand visionaries and proletariat workers while omitting the titans of industry.

- The Iron Horse is a complex film that celebrates diversity but also endorses empire and hegemony, reflecting the contradictions of America’s history.

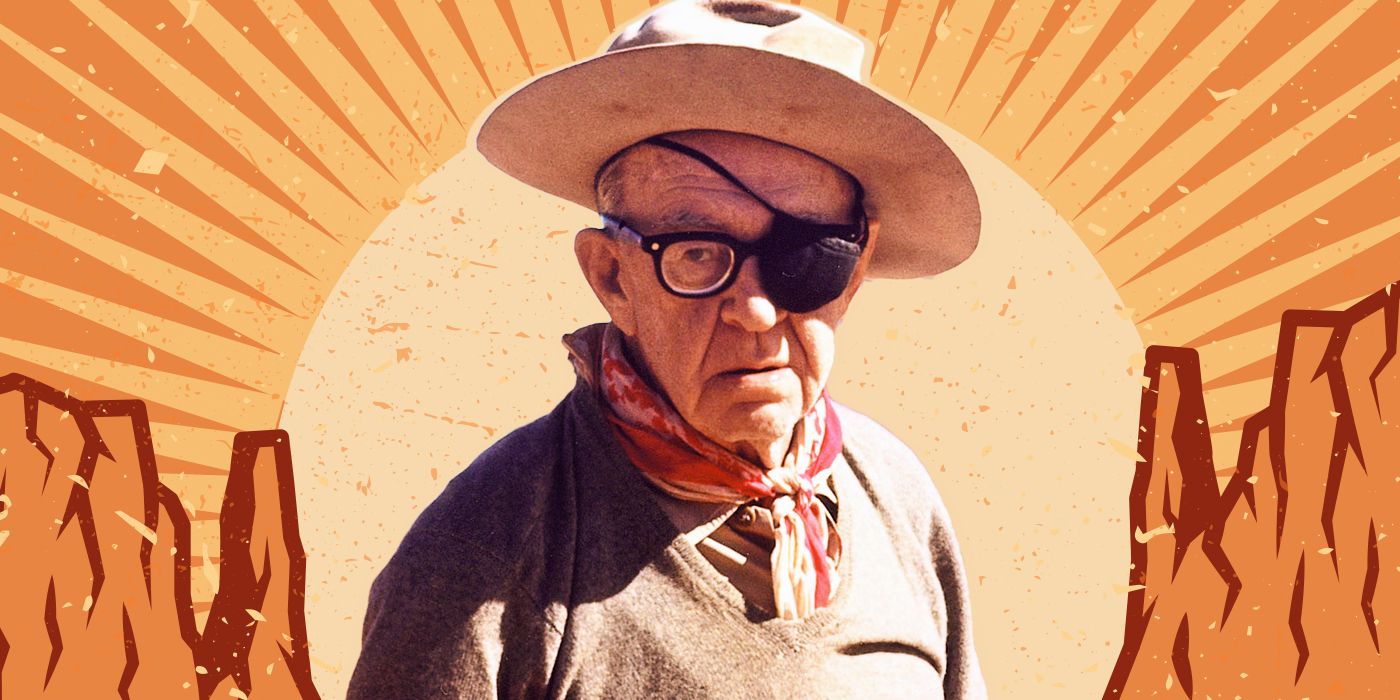

John Ford is recognized as one of the greatest filmmakers of all time, and his name epitomizes the grandiosity of so many classic Westerns. His distinct aesthetic sensibilities and thematic interest in American identity were influential and had a supreme impact on the trajectory of the genre throughout the 20th century. In fact, his influence reaches all the way to today sometimes in surprising places. He is credited with reinventing the genre on several occasions, perhaps most notably in his proto-revisionist self-critique The Searchers (1956), but what many people don’t know is that 99 years ago, in 1924, studios were dissatisfied with the waning popularity of Westerns. Before they could hang up their spurs for good, though, a young John Ford reinvigorated the genre with one of the grandest epics of the silent era. Not only did it save the genre’s market viability, but John Ford’s The Iron Horse set the mold for a hundred years of Westerns to come – for better and for worse.

William Fox, of the Fox Film Corporation, initially greenlighted the film as a response to the success of Paramount’s The Covered Wagon (James Cruz) one year prior. The Covered Wagon, a mega-budget epic about pioneers, was a success despite the diminishing interest in Western films at the time. Fox trusted the 29-year-old Ford to deliver a competitive picture that could keep Fox in the game in case Paramount’s success had been a flash in the pan. Ford had made a name for himself in the business, already with roughly 50 films under his belt, but The Iron Horse was his first shot at a major release.

The Iron Horse

After witnessing the murder of his father by a renegade as a boy, the grown-up Brandon helps to realize his father’s dream of a transcontinental railway.

What Is ‘The Iron Horse’ About?

Though the budget was nowhere near what James Cruz got to work with, it was nothing to scoff at, and John Ford had the resources to meticulously construct a portrait of 1860s American expansion. Many scenes are absolutely teeming with extras, and the technical fidelity of the film remains impressive to this day. The Iron Horse centers on an engaging melodrama about Davy Brandon (George O’Brien) who, after the death of his father, sets out to achieve his father’s dream of building the first transcontinental railroad. In the meantime, he also seeks revenge on his father’s killer and a romance with his childhood sweetheart Miriam Marsh (Madge Bellamy).

It is a rollicking epic melodrama with some surprisingly intense action for the time (although certainly not the grittiest Western of the era). The Iron Horse produced the most successful box office turnout of the year. It was Ford’s particular sensibility, though, which creatively revitalized the genre and made it so enduring for the next several decades.

John Ford Forged His Identity as a Filmmaker in ‘The Iron Horse’

From the opening moments of the film, it is clear where John Ford’s values lie. The credits give way to a dedication. Firstly, the film is dedicated to Abraham Lincoln, a man whom Ford’s admiration of saturates every moment of this film. He is credited simply as “the Builder,” positing Lincoln as the architect of the national project to which Ford’s patriotism is utterly devoted. Second, the film is dedicated to the engineers who literally constructed this vision of America. Before the film can even properly begin, Ford points to his admiration of grand visionaries and proletariat workers. Notably absent are the titans of industry who made their fortunes off of railroads and the like. This is an omission that colors the rest of the film’s story and themes, and which Ford continued to derive meaning from for the bulk of his career. The distinction between dreamers, workers, and profiteers will become more blurred and fraught in later films like The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962), but in The Iron Horse, it’s clear-cut.

In addition to the dedication at the beginning, another title card reads, “Accurate and faithful in every particular of fact and atmosphere is this pictorial history of the building of the first transcontinental railroad.” But accurate, this film is not. None of the principal characters in this film’s melodrama existed, and real-world figures like Buffalo Bill Cody (George Wagner) and Wild Bill Hickok (Jack Padjan) certainly never appeared in the capacity they do in the film. Still, “faithful” might be as apt a word as any to describe the meticulous, almost spiritual care with which Ford regards this story of American Unification. One scene depicts Lincoln (Charles Edward Bull) justifying his choice to fund the construction of the railroad in the midst of the Civil War. “We must not let problems of War blind us to greater problems of peace to come” he responds, “or we will have fought in vain.”

The Best Animated Western Borrows From a Beloved John Ford Classic

What sounds like a standard fish out of water story turns out to be so much more.

The film is often distracted from its central melodrama by details surrounding the construction of this railroad. Many scenes feature scores of multi-ethnic extras toiling away to build this epic project. A few of these extras were even real rail workers who contributed to the actual building of this railroad in the 1860s. The portrayal of some of these Irish, Italian, and Chinese workers can come across as stereotypical, but their inclusion still stands as notable for the time and serves to broaden the scope of Ford’s patriotism past interstitial politics and towards a grander, pseudo-religious invocation of American unity. However, it is this same divine idealism that gives way to the movie’s thornier subtext – the tacit affirmation of Manifest Destiny and assimilation.

‘The Iron Horse’s Main Romance Was Part of a More Fraught Story

If this movie is a microcosm of John Ford’s milieu, then John Ford is a microcosm of America’s many contradictions. In one scene, the workers are distraught because of a delay in their pay. When the sympathetic Miriam wades into the ruckus to remind them that they are working on something greater than themselves, they begin to see the light. For a future in this great country they are building, they can handle a delay. Knowing how America actually treated many of these groups of people, whether based on race or class or something else, this scene takes on a different tone. At best, it’s naive, but at worst it feels deliberately obfuscative. This is compounded by the film’s fraught (but uniquely fraught) treatment of Native American characters. At the beginning of the film, Davy’s father is killed by a band of Cheyenne Native Americans. Curiously, though, their bloodthirsty leader is only posing as a Cheyenne and is actually white. Eventually, the killer Bauman (Fred Kohler) ends up working for Miriam’s duplicitous fiancé to undermine the construction of the railroad for monetary gain, which brings Davy face to face with his father’s killer. Inevitably, of course, the bad guys are defeated, and the sweethearts reunited, but Bauman’s part reveals to the viewer a curious mandate implicit in The Iron Horse.

The Cheyenne in Bauman’s band are seemingly being duped into violence by a bad actor, who portrays them as, while abhorrently stereotyped, more sympathetic than many other films of this ilk. However, this sympathy belies a deeply held acceptance of American incursion into their land. Furthermore, Bauman seems to stand opposite the Italian and Chinese immigrants as an example of perverted assimilation. It’s as if Bauman is the way he is because he assimilated the wrong way.

The Iron Horse is a deeply complicated film. On one hand, it is a rousing stroke of technical virtuosity and a convicted celebration of the diversity at America’s core. On the other hand, it is a loud endorsement of empire and hegemony. Nonetheless, it is better not to overlook this ancient classic, because it is these exact contradictions that went on to define the Western as the genre revised itself repeatedly over the next decades. Even Ford himself would more critically scrutinize these thorny parts of himself in his darker, richer works. The Iron Horse is still absolutely worth a watch, if just for the spectacle, but it’s also worth examination. It captures an American spirit, which is a grand and often ugly thing, and that is just as relevant today as it was in 1924.

The Iron Horse is available to stream on Tubi in the U.S.