The alleged connection between the Mafia and two former NBA players — Hall of Famer Chauncey Billups and longtime veteran Damon Jones — began the way such things often do: through a little-known intermediary. That’s one of the ways organized crime finds its way into locker rooms and athletes’ inner circles — by degrees, through introductions that seem harmless enough.

What starts as a friendly poker night or an invitation from a trusted acquaintance can, before long, become something else entirely — a sticky web of influence and, soon enough, obligation, former prosecutors and those who study the Mob say.

In this case, prosecutors allege, the intermediary was Robert L. Stroud, a 67-year-old Louisville man with a criminal history. In 1994, Stroud killed a man during an evening playing cards and gambling at a home in Louisville, according to local outlet WAVE News. The outlet also reported that when Stroud was pulled over in 2001 for having expired tags, a police officer found “sports betting cards, dice, playing cards and what appeared to be gambling records” in the back seat.

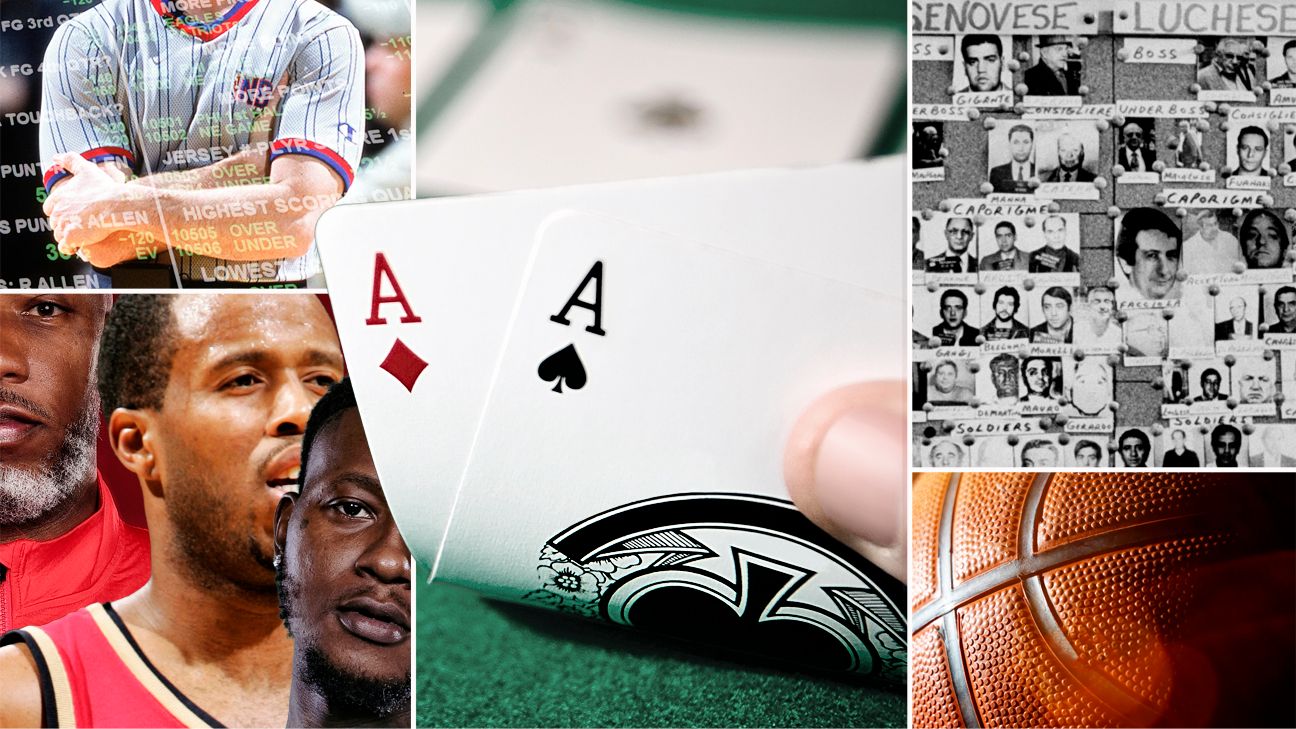

Stroud recruited Billups and Jones to take part in rigged poker games run by members of New York City’s most prominent crime families, according to an indictment and accompanying court documents made public last week.

“Stroud recruited former professional athletes, including defendants Billups and Damon Jones, into the conspiracy to lure wealthy victims into playing in the games,” according to a detention memo filed with the case. “For their role as ‘Face Cards’ and members of the cheating teams, Stroud paid them a portion of the criminal proceeds.”

Stroud, Billups and Jones were among 34 people, including Miami Heat guard Terry Rozier, arrested last week in connection with two overlapping investigations. One focused on an illegal sports betting scheme that allegedly relied on insider NBA information. The other involved high-stakes poker games linked to the Genovese, Gambino, Lucchese and Bonanno crime families. Prosecutors say Billups and Jones helped cheat participants out of more than $7 million through the use of X-ray tables, high-tech glasses and other futuristic tools. Billups’s attorney has denied wrongdoing by his client.

The charges have shaken the NBA, whose fabulously paid athletes seemingly have every incentive not to get involved in activities that could ruin their careers and reputations. It is unclear why Billups and Jones got involved with mob figures, as federal prosecutors allege. Billups earned more than $100 million over his decorated career, and nearly $5 million a year as coach of the Portland Trail Blazers. Jones, a former journeyman player and assistant coach, earned more than $22 million during his 11-year playing career.

“It’s hard to figure out why this happens,” said Keith Corbett, a lawyer and former head of the federal Organized Crime Strike Force in Detroit. He said that in past cases many gamblers have become ensnared with the mob because they are addicted to the action.

“There is always a certain lure where people want to do something that’s a little shady so they can get the cash and not report it,” he added. “Or they might owe these guys money for some reason, maybe because they bet with them.”

Scott Burnstein, a Mafia expert and founding editor of The Gangster Report, a website that tracks organized crime, said underworld figures often begin cultivating relationships with athletes early — at youth sports events and other loosely regulated venues.

“These showcase events, AAU basketball or 7-on-7 football tournaments are sometimes staged by criminals, or people close to criminals,” Burnstein said. “They then can later tap those relationships.”

Often, the ask is not one that would necessarily affect the outcome of a game. If a player is asked to get under a certain number of rebounds or play fewer minutes by faking an injury, it can be easy to rationalize, Burnstein said.

“They can do mental gymnastics to the point where they don’t really think they are affecting the outcome of a game,” he said. “So, they are morally in the clear in their minds.”

In the 1980s, Michael Franzese, then a capo in the Colombo crime family, bought a share in World Sports & Entertainment, a sports agency, with an eye on fostering tight relationships with athletes. The agency secretly signed top college players it believed would go pro.

“I did it because I wanted to get close to the athletes,” Franzese said. “We knew if we could get close to these guys, they are going to end up in trouble. If they gamble, they are going to come to us.”

Franzese’s move wasn’t just a personal hustle. It was part of a broader pattern that stretches across generations. Organized crime has long recognized the vulnerabilities of athletes — their money, their inexperience, their appetites — and found ways to exploit them.

“What people don’t understand about some athletes,” said Franzese, who has since spent decades speaking to sports leagues and the NCAA about gambling’s risks, “is that gambling is an extension of their competitive spirit. They want to raise the stakes. These guys go on a plane on a road trip and lose thousands of dollars.”

Mob figures have been drawn to big-time athletes for decades. In the 1960s, the collegiate and early professional careers of Hall of Famers Connie Hawkins and Roger Brown were derailed when investigators found they had associated with Jack Molinas, a former player turned mob-linked fixer. The two players were never arrested or indicted.

During the 1978-79 season, a group of Boston College basketball players was recruited to manipulate scores by Henry Hill and Jimmy “The Gent” Burke — associates of New York’s Lucchese crime family, later immortalized in “Goodfellas.” Hill’s group placed large wagers through mob-controlled bookmakers, carefully avoiding final outcomes and focusing on the spread to evade detection.

In the mid-2000s, NBA referee Tim Donaghy admitted to betting on games he officiated and feeding insider information to professional gamblers, some with organized crime ties. Even tennis and boxing, with their individual athletes and opaque judging, have periodically drawn mob attention — from fixed fights in Las Vegas to match manipulation on international betting exchanges.

“People who want to fix games would make it their business to cultivate relationships so these kids would be beholden to them,” said Edward A. McDonald, who led the prosecution of the Boston College point-shaving case. “They make sure they are friendly with these kids, and the next thing you know they are in their world.”

While the Mafia is widely perceived as waning, people who closely follow its activities say it has only evolved. There is less violence, some say, and more sophistication. “I don’t believe they’re at the apex of power like we were during our time,” Franzese said. “But they’re not going away.”

But, as always, gambling remains one of the Mob’s most profitable activities. Even with the proliferation of legalized wagering, underground betting still has an unshakeable allure.

Dan E. Moldea, the investigative reporter whose 1989 book “Interference: How Organized Crime Influences Professional Football” stirred both outrage and denial across the NFL, predicted in the book that the spread of legal sports betting would, in turn, fuel a surge in illegal gambling. “You can get a bigger bang for your buck from Charlie, the friendly neighborhood mob bookmaker at the corner bar,” Moldea said. “And Charlie will give you credit.”

While professional athletes can make huge incomes, their careers are often short and their bankrolls not endless. Records show Jones has filed for bankruptcy twice in Texas, in 2013 and 2015, though both petitions were dismissed. In 2015, he claimed to have liabilities ranging from $500,000 to $1 million and assets between $100,001 and $500,000. Among his creditors was the Bellagio casino in Las Vegas, which said Jones owed more than $47,000.

In a September 2023 text message copied in court papers, Jones asked Stroud — the man prosecutors allege recruited him and Billups into the poker scheme — for an advance before a game.

“I don’t know how much the job pays tomorrow but can I get a 10k advance on it??” Jones asked. “GOD really blessed me that u have action for me cause I needed it today bad.”