CNN

—

Effie Schnacky was wheezy and lethargic instead of being her normal, rambunctious self one February afternoon. When her parents checked her blood oxygen level, it was hovering around 80% – dangerously low for the 7-year-old.

Her mother, Jaimie, rushed Effie, who has asthma, to a local emergency room in Hudson, Wisconsin. She was quickly diagnosed with pneumonia. After a couple of hours on oxygen, steroids and nebulizer treatments with little improvement, a physician told Schnacky that her daughter needed to be transferred to a children’s hospital to receive a higher level of care.

What they didn’t expect was that it would take hours to find a bed for her.

Even though the respiratory surge that overwhelmed doctor’s offices and hospitals last fall is over, some parents like Schnacky are still having trouble getting their children beds in a pediatric hospital or a pediatric unit.

The physical and mental burnout that occurred during the height of the Covid-19 pandemic has not gone away for overworked health care workers. Shortages of doctors and technicians are growing, experts say, but especially in skilled nursing. That, plus a shortage of people to train new nurses and the rising costs of hiring are leaving hospitals with unstaffed pediatric beds.

But a host of reasons building since well before the pandemic are also contributing. Children may be the future, but we aren’t investing in their health care in that way. With Medicaid reimbursing doctors at a lower rate for children, hospitals in tough situations sometimes put adults in those pediatric beds for financial reasons. And since 2019, children with mental health crises are increasingly staying in emergency departments for sometimes weeks to months, filling beds that children with other illnesses may need.

“There might or might not be a bed open right when you need one. I so naively just thought there was plenty,” Schnacky told CNN.

The number of pediatric beds decreasing has been an issue for at least a decade, said Dr. Daniel Rauch, chair of the Committee on Hospital Care for the American Academy of Pediatrics.

By 2018, almost a quarter of children in America had to travel farther for pediatric beds as compared to 2009, according to a 2021 paper in the journal Pediatrics by lead author Dr. Anna Cushing, co-authored by Rauch.

“This was predictable,” said Rauch, who has studied the issue for more than 10 years. “This isn’t shocking to people who’ve been looking at the data of the loss in bed capacity.”

The number of children needing care was shrinking before the Covid-19 pandemic – a credit to improvements in pediatric care. There were about 200,000 fewer pediatric discharges in 2019 than there were in 2017, according to data from the US Department of Health and Human Services.

“In pediatrics, we have been improving the ability we have to take care of kids with chronic conditions, like sickle cell and cystic fibrosis, and we’ve also been preventing previously very common problems like pneumonia and meningitis with vaccination programs,” said Dr. Matthew Davis, the pediatrics department chair at Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago.

Pediatrics is also seasonal, with a typical drop in patients in the summer and a sharp uptick in the winter during respiratory virus season. When the pandemic hit, schools and day cares closed, which slowed the transmission of Covid and other infectious diseases in children, Davis said. Less demand meant there was less need for beds. Hospitals overwhelmed with Covid cases in adults switched pediatric beds to beds for grownups.

Only 37% of hospitals in the US now offer pediatric services, down from 42% about a decade ago, according to the American Hospital Association.

While pediatric hospital beds exist at local facilities, the only pediatric emergency department in Baltimore County is Greater Baltimore Medical Center in Towson, Maryland, according to Dr. Theresa Nguyen, the center’s chair of pediatrics. All the others in the county, which has almost 850,000 residents, closed in recent years, she said.

The nearby MedStar Franklin Square Medical Center consolidated its pediatric ER with the main ER in 2018, citing a 40% drop in pediatric ER visits in five years, MedStar Health told CNN affiliate WBAL.

In the six months leading up to Franklin Square’s pediatric ER closing, GBMC admitted an average of 889 pediatric emergency department patients each month. By the next year, that monthly average jumped by 21 additional patients.

“Now we’re seeing the majority of any pediatric ED patients that would normally go to one of the surrounding community hospitals,” Nguyen said.

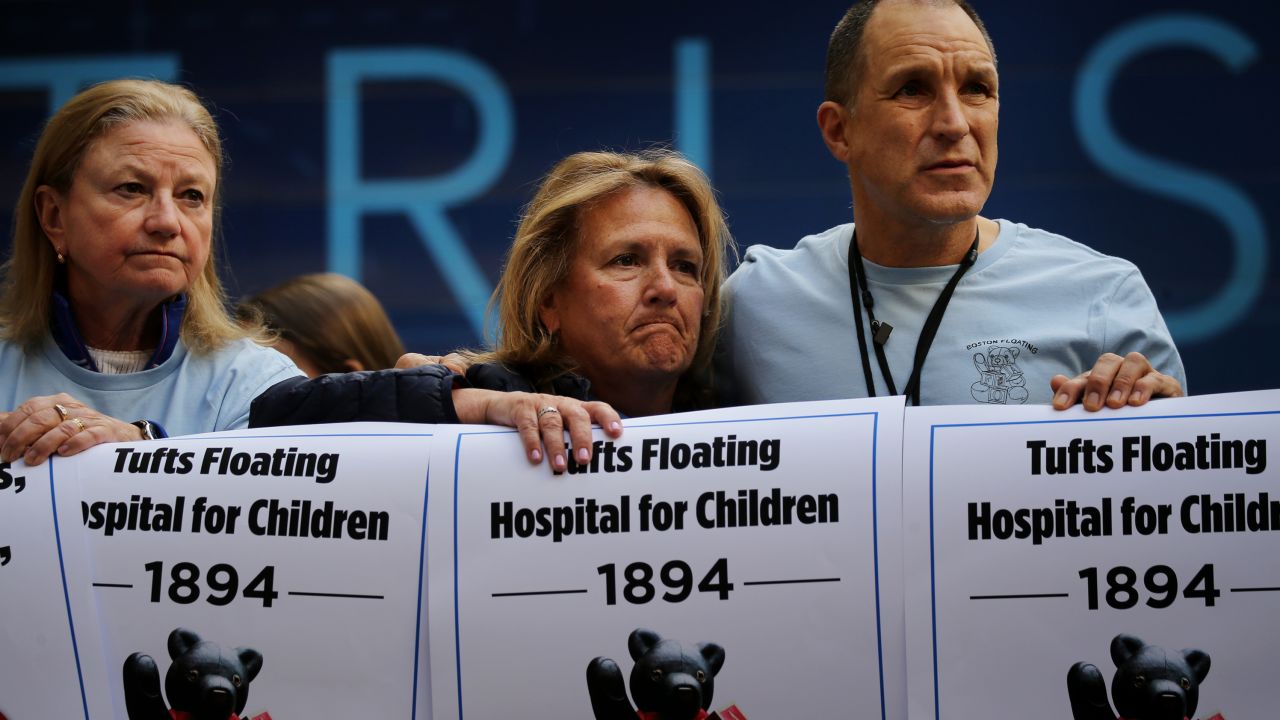

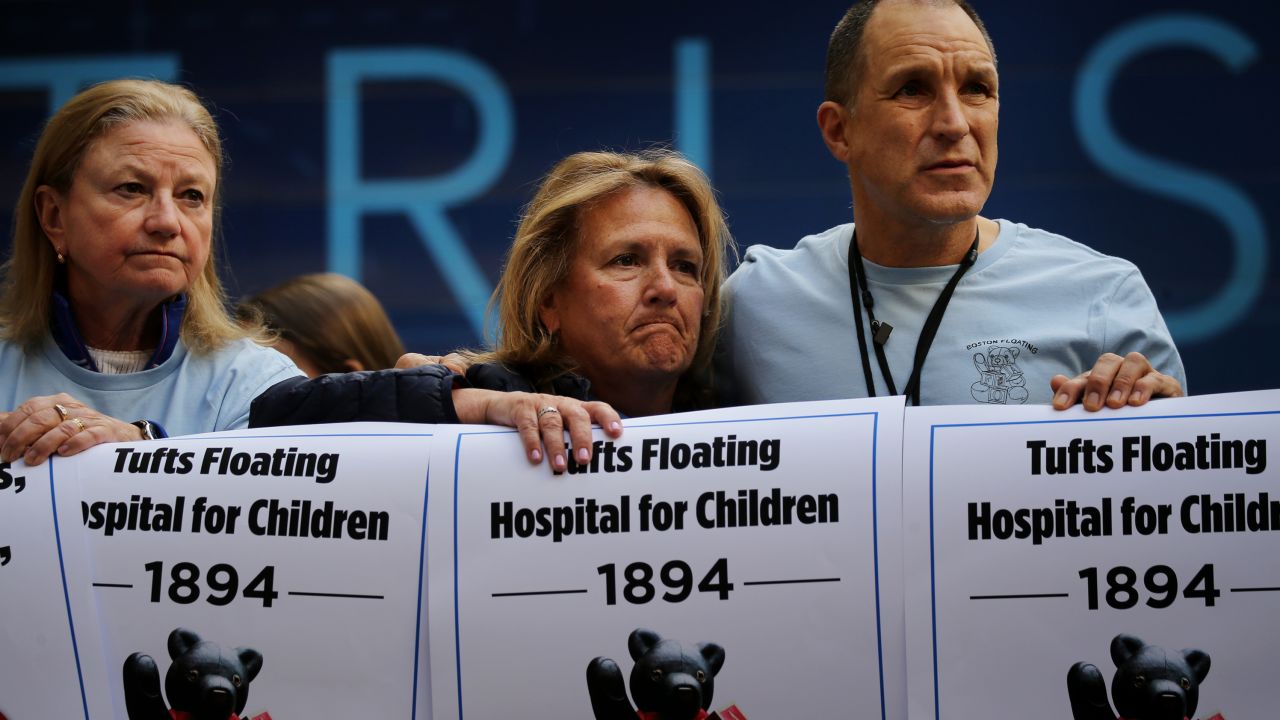

In July, Tufts Medical Center in Boston converted its 41 pediatric beds to treat adult ICU and medical/surgical patients, citing the need to care for critically ill adults, the health system said.

In other cases, it’s the hospitals that have only 10 or so pediatric beds that started asking the tough questions, Davis said.

“Those hospitals have said, ‘You know what? We have an average of one patient a day or two patients a day. This doesn’t make sense anymore. We can’t sustain that nursing staff with specialized pediatric training for that. We’re going to close it down,’” Davis said.

Saint Alphonsus Regional Medical Center in Boise closed its pediatric inpatient unit in July because of financial reasons, the center told CNN affiliate KBOI. That closure means patients are now overwhelming nearby St. Luke’s Children’s Hospital, which is the only children’s hospital in the state of Idaho, administrator for St. Luke’s Children’s Katie Schimmelpfennig told CNN. Idaho ranks last for the number of pediatricians per 100,000 children, according to the American Board of Pediatrics in 2023.

The Saint Alphonsus closure came just months before the fall, when RSV, influenza and a cadre of respiratory viruses caused a surge of pediatric patients needing hospital care, with the season starting earlier than normal.

The changing tide of demand engulfed the already dwindling supply of pediatric beds, leaving fewer beds available for children coming in for all the common reasons, like asthma, pneumonia and other ailments. Additional challenges have made it particularly tough to recover.

Another factor chipping away at bed capacity over time: Caring for children pays less than caring for adults. Lower insurance reimbursement rates mean some hospitals can’t afford to keep these beds – especially when care for adults is in demand.

Medicaid, which provides health care coverage to people with limited income, is a big part of the story, according to Joshua Gottlieb, an associate professor at the University of Chicago Harris School of Public Policy.

“Medicaid is an extremely important payer for pediatrics, and it is the least generous payer,” he said. “Medicaid is responsible for insuring a large share of pediatric patients. And then on top of its low payment rates, it is often very cumbersome to deal with.”

Medicaid reimburses children’s hospitals an average of 80% of the cost of the care, including supplemental payments, according to the Children’s Hospital Association, a national organization which represents 220 children’s hospitals. The rate is far below what private insurers reimburse.

More than 41 million children are enrolled in Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program, according to Kaiser Family Foundation data from October. That’s more than half the children in the US, according to Census data.

At Children’s National Hospital in Washington, DC, about 55% of patients use Medicaid, according to Dr. David Wessel, the hospital’s executive vice president.

“Children’s National is higher Medicaid than most other children’s hospitals, but that’s because there’s no safety net hospital other than Children’s National in this town,” said Wessel, who is also the chief medical officer and physician-in-chief.

And it just costs more to care for a child than an adult, Wessel said. Specialty equipment sized for smaller people is often necessary. And a routine test or exam for an adult is approached differently for a child. An adult can lie still for a CT scan or an MRI, but a child may need to be sedated for the same thing. A child life specialist is often there to explain what’s going on and calm the child.

“There’s a whole cadre of services that come into play, most of which are not reimbursed,” he said. “There’s no child life expert that ever sent a bill for seeing a patient.”

Low insurance reimbursement rates also factor into how hospital administrations make financial decisions.

“When insurance pays more, people build more health care facilities, hire more workers and treat more patients,” Gottlieb said.

“Everyone might be squeezed, but it’s not surprising that pediatric hospitals, which face [a] lower, more difficult payment environment in general, are going to find it especially hard.”

Dr. Benson Hsu is a pediatric critical care provider who has served rural South Dakota for more than 10 years. Rural communities face distinct challenges in health care, something he has seen firsthand.

A lot of rural communities don’t have pediatricians, according to the American Board of Pediatrics. It’s family practice doctors who treat children in their own communities, with the goal of keeping them out of the hospital, Hsu said. Getting hospital care often means traveling outside the community.

Hsu’s patients come from parts of Nebraska, Iowa and Minnesota, as well as across South Dakota, he said. It’s a predominantly rural patient base, which also covers those on Native American reservations.

“These kids are traveling 100, 200 miles within their own state to see a subspecialist,” Hsu said, referring to patients coming to hospitals in Sioux Falls. “If we are transferring them out, which we do, they’re looking at travels of 200 to 400 miles to hit Omaha, Minneapolis, Denver.”

Inpatient pediatric beds in rural areas decreased by 26% between 2008 and 2018, while the number of rural pediatric units decreased by 24% during the same time, according to the 2021 paper in Pediatrics.

“It’s bad, and it’s getting worse. Those safety net hospitals are the ones that are most at risk for closure,” Rauch said.

In major cities, the idea is that a critically ill child would get the care they need within an hour, something clinicians call the golden hour, said Hsu, who is the critical care section chair at the American Academy of Pediatrics.

“That golden hour doesn’t exist in the rural population,” he said. “It’s the golden five hours because I have to dispatch a plane to land, to drive, to pick up, stabilize, to drive back, to fly back.”

When his patients come from far away, it uproots the whole family, he said. He described families who camp out at a child’s bedside for weeks at a time. Sometimes they are hundreds of miles from home, unlike when a patient is in their own community and parents can take turns at the hospital.

“I have farmers who miss harvest season and that as you can imagine is devastating,” Hsu said. “These aren’t office workers who are taking their computer with them. … These are individuals who have to live and work in their communities.”

Back at GBMC in Maryland, an adolescent patient with depression, suicidal ideation and an eating disorder was in the pediatric emergency department for 79 days, according to Nguyen. For months, no facility had a pediatric psychiatric bed or said it could take someone who needed that level of care, as the patient had a feeding tube.

“My team of physicians, social workers and nurses spend a significant amount of time every day trying to reach out across the state of Maryland, as well as across the country now to find placements for this adolescent,” Nguyen said before the patient was transferred in mid-March. “I need help.”

Nguyen’s patient is just one of the many examples of children and teens with mental health issues who are staying in emergency rooms and sometimes inpatient beds across the country because they need help, but there isn’t immediately a psychiatric bed or a facility that can care for them.

It’s a problem that began before 2020 and grew worse during the pandemic, when the rate of children coming to emergency rooms with mental health issues soared, studies show.

Now, a nationwide shortage of beds exists for children who need mental health help. A 2020 federal survey revealed that the number of residential treatment facilities for children fell 30% from 2012.

“There are children on average waiting for two weeks for placement, sometimes longer,” Nguyen said of the patients at GBMC. The pediatric emergency department there had an average of 42 behavioral health patients each month from July 2021 through December 2022, up 13.5% from the same period in 2017 to 2018, before the pandemic, according to hospital data.

When there are mental health patients staying in the emergency department, that can back up the beds in other parts of the hospital, creating a downstream effect, Hsu said.

“For example, if a child can’t be transferred from a general pediatric bed to a specialized mental health center, this prevents a pediatric ICU patient from transferring to the general bed, which prevents an [emergency department] from admitting a child to the ICU. Health care is often interconnected in this fashion,” Hsu said.

“If we don’t address the surging pediatric mental health crisis, it will directly impact how we can care for other pediatric illnesses in the community.”

So, what can be done to improve access to pediatric care? Much like the reasons behind the difficulties parents and caregivers are experiencing, the solutions are complex:

- A lot of it comes down to money

Funding for children’s hospitals is already tight, Rauch said, and more money is needed not only to make up for low insurance reimbursement rates but to competitively hire and train new staff and to keep hospitals running.

“People are going to have to decide it’s worth investing in kids,” Rauch said. “We’re going to have to pay so that hospitals don’t lose money on it and we’re going to have to pay to have staff.”

Virtual visits, used in the right situations, could ease some of the problems straining the pediatric system, Rauch said. Extending the reach of providers would prevent transferring a child outside of their community when there isn’t the provider with the right expertise locally.

- Increased access to children’s mental health services

With the ongoing mental health crisis, there’s more work to be done upstream, said Amy Wimpey Knight, the president of CHA.

“How do we work with our school partners in the community to make sure that we’re not creating this crisis and that we’re heading it off up there?” she said.

There’s also a greater need for services within children’s hospitals, which are seeing an increase in children being admitted with behavioral health needs.

“If you take a look at the reasons why kids are hospitalized, meaning infections, diabetes, seizures and mental health concerns, over the last decade or so, only one of those categories has been increasing – and that is mental health,” Davis said. “At the same time, we haven’t seen an increase in the number of mental health hospital resources dedicated to children and adolescents in a way that meets the increasing need.”

Most experts CNN spoke to agreed: Seek care for your child early.

“Whoever is in your community is doing everything possible to get the care that your child needs,” Hsu said. “Reach out to us. We will figure out a way around the constraints around the system. Our number one concern is taking care of your kids, and we will do everything possible.”

Nguyen from GBMC and Schimmelpfennig from St. Luke’s agreed with contacting your primary care doctor and trying to keep your child out of the emergency room.

“Anything they can do to stay out of the hospital or the emergency room is both financially better for them and better for their family,” Schimmelpfennig said.

Knowing which emergency room or urgent care center is staffed by pediatricians is also imperative, Rauch said. Most children visit a non-pediatric ER due to availability.

“A parent with a child should know where they’re going to take their kid in an emergency. That’s not something you decide when your child has the emergency,” he said.

After Effie’s first ambulance ride and hospitalization last month, the Schnacky family received an asthma action plan from the pulmonologist in the ER.

It breaks down the symptoms into green, yellow and red zones with ways Effie can describe how she’s feeling and the next steps for adults. The family added more supplies to their toolkit, like a daily steroid inhaler and a rescue inhaler.

“We have everything an ER can give her, besides for an oxygen tank, at home,” Schnacky said. “The hope is that we are preventing even needing medical care.”