The legend of the Sibylline Books tells us that in an ancient city, a woman offered to sell its citizens 12 books containing all the knowledge and wisdom in the world, for a high price. They refused, thought her request ridiculous, so she burned half of the books right then and there, and then offered to sell the remaining six for double the price. The citizens laughed at her, a little uneasily this time. She burned three, offering the remainder, but doubling the price again. Somewhat reluctantly – times were hard, their troubles seemed to be multiplying – they dismissed her once more. Finally, when there was only one book left, the citizens paid the extraordinary price the woman now asked, and she left them alone, to manage as best they could with one-twelfth of all the knowledge and wisdom in the world.

Books carry knowledge. They are pollinators of our minds, spreading self-replicating ideas through space and time. We forget what a miracle it is that marks on a page or screen can enable communication from one brain to another on the far side of the globe, or the other end of the century.

More like this:

– The radical books rewriting sex

– Why the world’s most difficult novel is so rewarding

– The overlooked masterpieces of 1922

Books are, as Stephen King put it, “a uniquely portable magic” – and the portable part is as important as the magic. A book can be taken away, kept hidden, your own private store of knowledge. (My son’s personal diary has an ineffectual – but symbolically important – padlock.) The power of the words inside books is so great that it’s long been custom for some words to be blanked out: such as swear words, as anyone encountering a “d—-d” in a 19th-Century novel will know; or words too dangerously powerful to be written down, like the name of God in some religious texts.

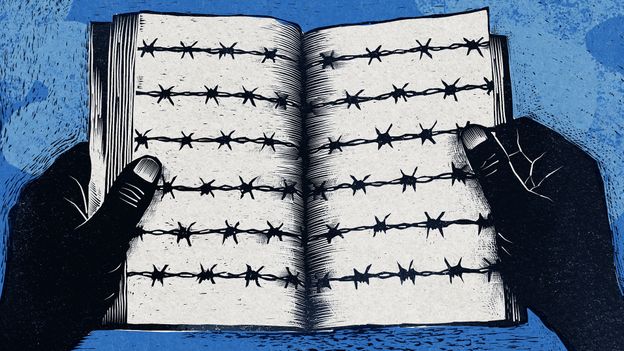

Books carry knowledge, and knowledge is power, which makes books a threat to authorities – governments and self-appointed leaders alike – who want to have a monopoly on knowledge and to control what their citizens think. And the most efficient way to exert this power over books is to ban them.

Banning books has a long and ignoble history, but it is not dead: it remains a thriving industry. This week is the 40th anniversary of Banned Books Week, an annual event “celebrating the freedom to read.” Banned Books Week was launched in 1982 in response to a rise in challenges to books in schools, libraries and bookstores.