(Image credit: Edward Burtynsky, Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto / Flowers Gallery, London)

Canadian photographer Edward Burtynsky discusses his startling and unexpectedly sublime photos – ‘an extended lament for the loss of nature’ – with Gaia Vince.

F

For more than 40 years, the Canadian photographer Edward Burtynsky has recorded the impact of humans on the Earth in large-scale images that often resemble abstract paintings. The writer Gaia Vince, whose book Nomad Century was published in 2022, interviewed Burtynsky for BBC Culture about his latest project, African Studies.

African Studies is now collected in a book and is on display at Flowers Gallery, Hong Kong until 20 May 2023.

Gaia Vince: With your pictures we see the results of our consumption habits or our lifestyles, in our cities. We see the results of that far, far away in a natural landscape made unnatural by our activities. Can you tell me about African Studies?

Edward Burtynsky: I was reading that China was beginning to offshore to Africa, and I thought that would be really interesting to follow. Overall it’s been a decade-long project, researching and then photographing in 10 countries. I started in Kenya, and then Ethiopia, then Nigeria, and then I went to South Africa.

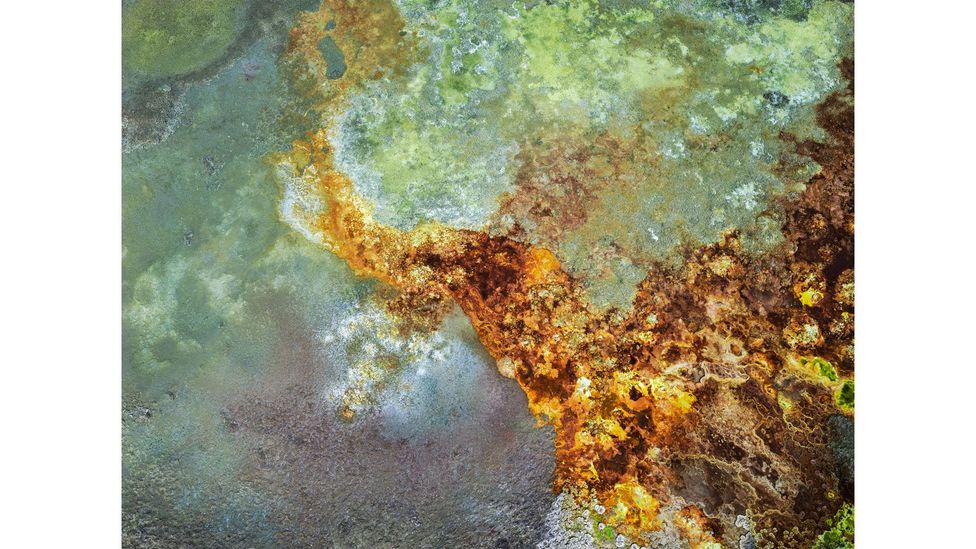

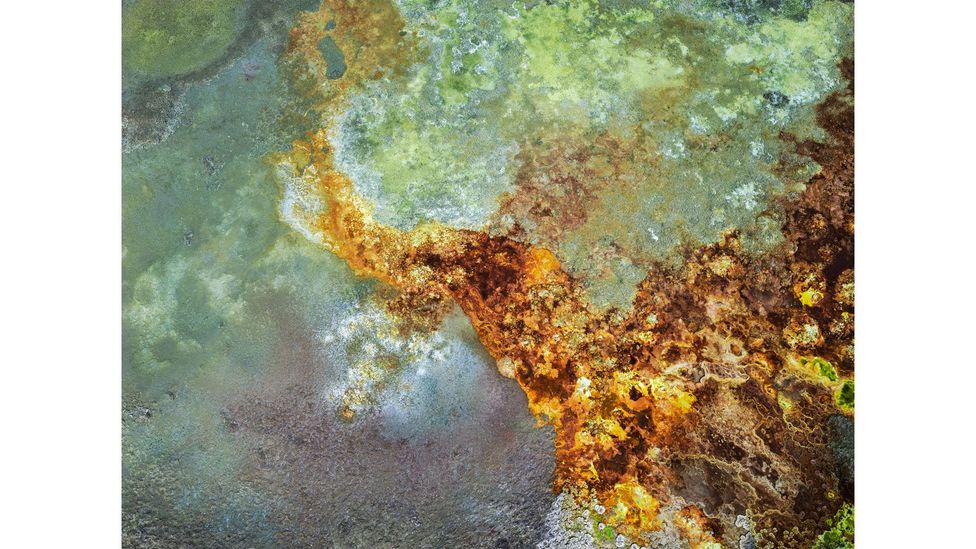

Sulfur Springs #1, Danakil Depression, Ethiopia, 2018 (Credit: Edward Burtynsky, Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto / Flowers Gallery, London)

GV: I noticed that you went to the Danakil Depression in Ethiopia – tell me about that.

EB: All our drone equipment wasn’t working because we were 400 feet below sea level. So the drone GPS was saying: ‘You’re not supposed to be here. You’re at the bottom of the ocean’. We had to turn off our GPS because we couldn’t get it to calibrate, it didn’t know where it was.

The Danakil Depression is a vast area covering about 200km by 50km. It’s known as one of the hottest places in the world and has been referred to as ‘hell on Earth’. I’ve never worked in temperatures over 50C. At night, it was 40C – even 40 is almost unbearable. And we were sleeping outside because there are no buildings, there are no interior spaces. We spent three days there shooting; in the mornings we would get up and then drive as far as 25km to get to our locations. One such location was Dallol, a volcanic hellscape of sulfurous springs. Getting to it required that we carry all our heavy equipment while climbing jagged rocks for about 1.5km.

Camel Caravan #1, Danakil Depression, Ethiopia, 2018 (Credit: Edward Burtsynky, Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto / Flowers Gallery, London)

GV: It’s physically extremely demanding what you’re doing.

EB: That was! Yeah, it is often and you’re working with both the late evening light and the early morning light. So you’re working both ends of the day and you really don’t get a lot of rest in between that because to get to the location in the morning with that early light, you have to be up usually an hour and a half before that happens. But you do whatever you need to do. When I’m in that space, I’m just like, ‘here’s the problem, here’s what I want to do, what’s it going to take?’

Sulfur Springs #2, Danakil Depression, Ethiopia, 2018 (Credit: Edward Burtynsky, Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto / Flowers Gallery, London)

GV: Africa is the last big continent that has large amounts of wilderness left. Partly because of colonialism and other extractive industries from the Global North, the industrial revolution in Africa is happening now. So there’s this juxtaposition between that wild landscape and these very synthetic landscapes that humans have created – how do you understand that yourself?

EB: The African continent has a lot of wilderness left and there are a lot of resources, like the discovery of oil in Tanzania and northern Kenya and other places. There’s a big rush for oil pipelines to be going in there. Particularly with China’s involvement, there are a lot of plays to build infrastructure in exchange for access to resources, whether it’s farmland for food security, whether it’s oil, yellowcake uranium, etc.

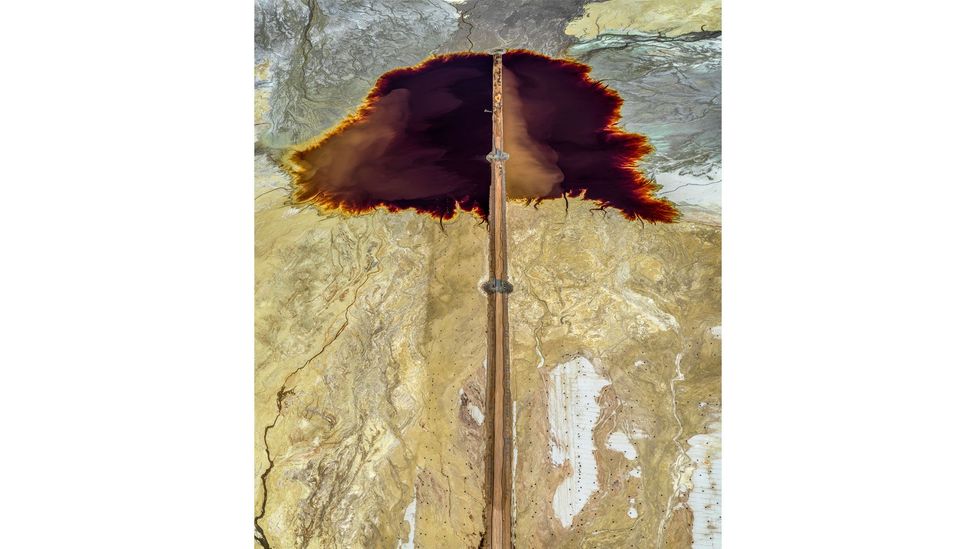

Uranium Tailings #13, Husab Uranium Mine, Namibia (Credit: Edward Burtynsky, Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto / Flowers Gallery, London)

It’s like economic colonialism. I don’t think they want full control of these countries. They want an economic advantage, they want the resources and they want the opportunity those resources provide. For example, the Chinese own the largest deposit of uranium yellowcake in all of the African continent – I photographed that mine.

GV: I also saw your incredible photographs from the shoe factory in Ethiopia. It looks completely transposed from China to Africa.

Huajian Shoe Factory #1, Dukem, Ethiopia, 2018 (Credit: Edward Burtynsky, Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto / Flowers Gallery, London)

EB: Some of the photos were taken in Hawassa, which is a 200-acre Special Economic Zone, like Shenzhen in China. The Chinese built what they call sheds, which are more like warehouses. They built 54 of these sheds, with the roadway. So you can look at that picture – with the roadways, with the lighting, with the plumbing, with everything. All done, start to finish, 54 of these were built within one year – all the structures were brought by ship and then by rails into Ethiopia and erected like a Meccano set. And when I was there, they were filling these sheds with sewing machines and textile makers.

Hawassa Industrial Park #1, Awassa, Ethiopia, 2018 (Credit: Edward Burtynsky, Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto / Flowers Gallery, London)

GV: The industrial revolution started in England and the factories of the North, and still if we dig down, it’s just completely polluted soils and landscapes, and then that was offshored to poorer countries and so on… That cycle is hitting Africa. But where is it going to be offshored next? We can’t just keep offshoring. There isn’t another place.

EB: I often say that ‘this is the end of the road’. We’re meeting the end of globalisation and where you can go. And it has to leave China because they’re gagging on the pollution. Their water’s been completely polluted. The labour force has said: ‘I’m not going to work for cheap wages like this anymore.’

So instead the Chinese are training textile workers – mainly female – in Ethiopia, and Senegal, and within two or three months, those girls are behind sewing machines and on par with Chinese production rates and what they would’ve expected out of a Chinese factory. That’s their goal. And they’re training these young 16, 17-year-olds, taking them away from their families and then putting them right into the sewing machine sweatshop.

C&H Garments #3, Diamniadio Industrial City, Senegal, 2019 (Credit: Edward Burtynsky, Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto / Flowers Gallery, London)

GV: At the heart of your images, they’re very political, aren’t they?

EB: Well, I’ve been following globalism but I started with the whole idea of just looking at nature. That’s the category where I began, the idea of ‘who’s paying the price for our population growth and our success as a species?’ Broadly speaking, it’s nature. It’s the animals, the trees, the prairies, the wetlands, the oceans – that’s where the price is being paid, you know, and they’re all being pushed back. These are all the natural environments on the planet that we used to coexist with, that we’re now totally overwhelming in a way. So nature’s at the core – and all my work is really kind of an extended lament for the loss of nature.

N4 Road #1, Nguekhokhe, Senegal, 2019 (Credit: Edward Burtynsky, Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto / Flowers Gallery, London)

GV: Do you see yourself as holding up a mirror to the world as it changes, and as it becomes more human-dominated? Or do you see yourself as an activist – are you trying to prompt change?

EB: Well, I wouldn’t say activist – somebody once mentioned ‘artivist’ and I liked that better. ‘Activist’ seems to lean more into the direct political discourse – I don’t want to turn my work into an indictment, a two-dimensional kind of blunt tool to say, ‘this is wrong, this is bad, cease and desist’. I don’t think it’s that simple.

I think all my work, in a way, is showing us at work in ‘business as usual’ mode. I’m trying to show us ‘these are all actual parts of our world that are unfolding every day in order to support what is now 8bn people, wanting to have more and more of what we in the West have’. I understood 40 years ago, when I started looking at the population growth, and I got a chance to see the scale of production, that this is only going to get bigger. Our cities are only going to get more massive.

I decided to continue looking at the human expansion, the footprint, and how we’re reaching around the world, pushing nature back to build our factories, to build our cities, to farm – we live on a finite planet.

Magadi Soda Company #1, Lake Magadi, Kenya, 2017 (Credit: Edward Burtynsky, Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto / Flowers Gallery, London)

Going back to your original question, I think the term ‘revelatory’ versus ‘accusatory’ has always been something that I’m comfortable with, in that I’m pulling the curtain back and saying, ‘Look, guys, you know, we can still turn this ship around if we’re smart about it. But failing that, we’re gambling. We’re betting the planet.’

GV: What do you think the odds are?

EB: The Canadian environmental scientist David Suzuki once said it really well. He used the metaphor of Wile E. Coyote chasing the Road Runner – how all of a sudden the Road Runner can make a sharp turn but Wile E. doesn’t change course, he keeps going and runs himself right over a canyon. Suzuki said: ‘We are currently over the air with our feet running. And the only question is, are we going to fall 10 feet or 500 feet?’

Salt Ponds #6, near Tikat Banguel, Senegal, 2019 (Credit: Edward Burtynsky, Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto / Flowers Gallery, London)

GV: I think one of the things your pictures show us is that we are already falling. We don’t see this destruction in our nice air-conditioned offices in the US or in London. We don’t necessarily feel the shock of that fall. But for people who are living on the edge, who are living in the Niger Delta, for example, they’re already very much experiencing this fall.

Oil bunkering #2, Niger Delta, Nigeria, 2016 (Credit: Edward Burtynsky, Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto / Flowers Gallery, London)

And I think that’s something that your pictures really show. They bring a more planetary perspective, but they bring it in a way that we don’t generally get to see. And one of the reasons for that is that they are genuinely a different perspective. There is a bird’s eye view there, an aerial shot, so we see something that we might only glimpse in a news reel or an image in a travel book. They bring it in, in a way that you can somehow see that scale.

Salt Pans #32, Walvis Bay, Namibia, 2018 (Credit: Edward Burtynsky, Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto / Flowers Gallery, London)

EB: Photography has the capacity to do that, if you understand how it works and how to use it. But we don’t actually normally see the world that way, from above. If you look at a Peregrine falcon, they have the highest resolution of any retina of any animal in the world, and scientists are unpacking it to understand how to make sensors for cameras. In a similar way, photography makes everything sharp and present all at once. Seeing my work at scale, as big prints, you can walk up to them and you can look at the tire tracks and you can see the small truck or person working in the corner.

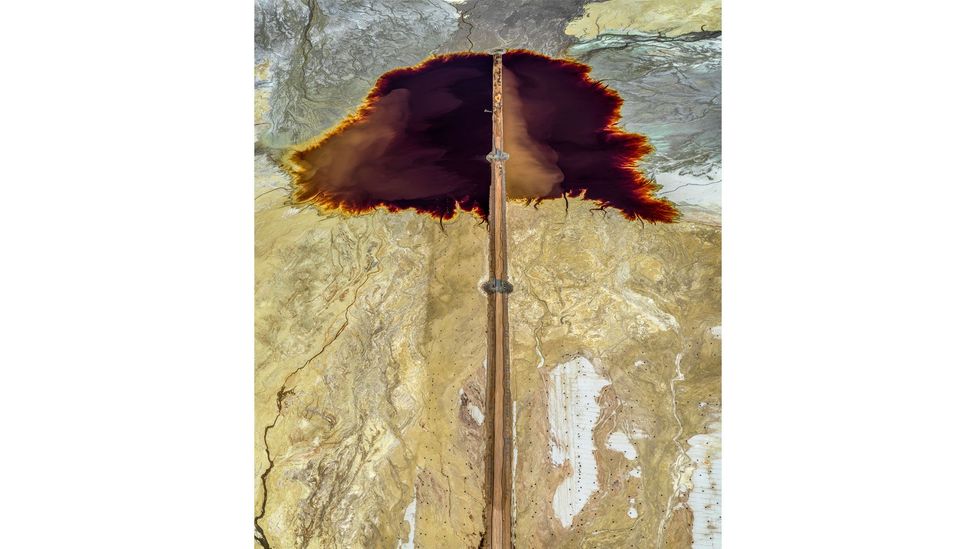

Tailings Pond #4, Botswana Ash Company, Sua Pan, Botswana, 2019 (Credit: Edward Burtynsky, Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto / Flowers Gallery, London)

GV: That is the extraordinary power of your pictures – there is this huge scale. And at first, it’s like an artwork – it looks artistic, abstract, perhaps a painting because you can pick out patterns. And then you start to realise: ‘Actually no, this is something that’s either natural or it’s human made’. And then you realise these tiny little ants or these little markings are enormous stone-moving machines or skyscrapers or something really big. But you manage to bring that absolute precision and detail and focus into something that is really huge. How do you do that?

EB: By and large I’ve used super high-resolution digital cameras for the singular shots. You can also lock drones up in the air, it’ll hold the camera even if it’s windy up there; it will constantly be correcting for being buffeted. And then with that precision, with that ability to hold it there, I can use a longer lens and do a group of shots of that subject. I’m controlling the high-resolution camera through a video on the ground – the camera could be 1000 feet away – and then I can carefully shoot all the frames that I need to later stitch together in Photoshop. Most of my work is single shots on high-resolution cameras. The camera I use now is 150-megapixel.

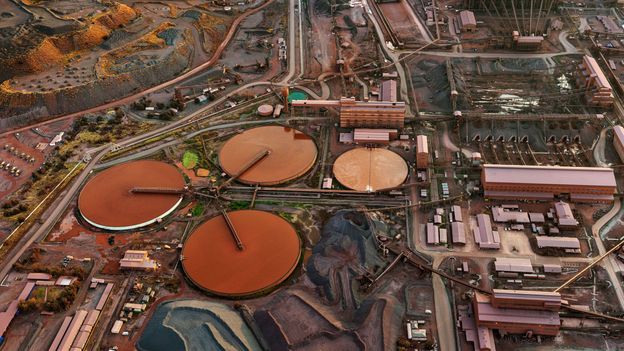

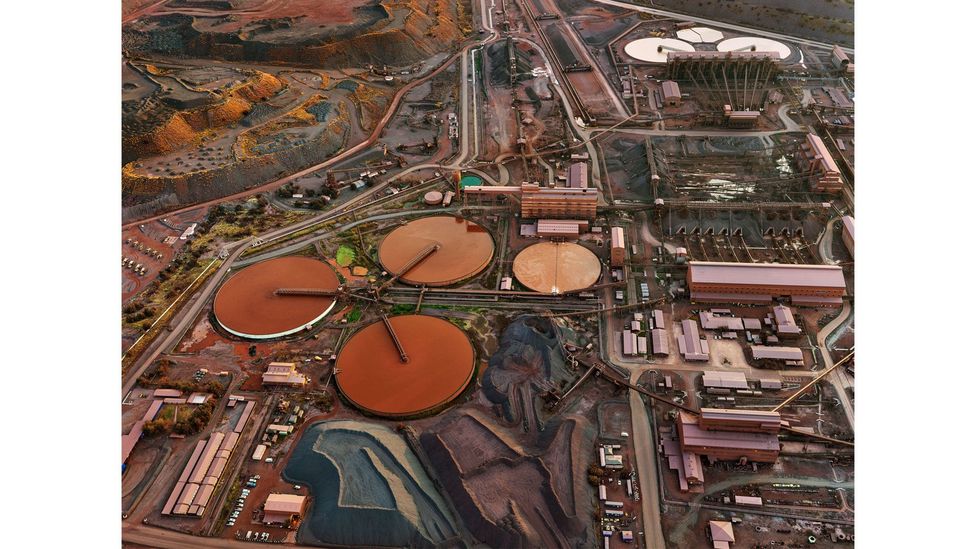

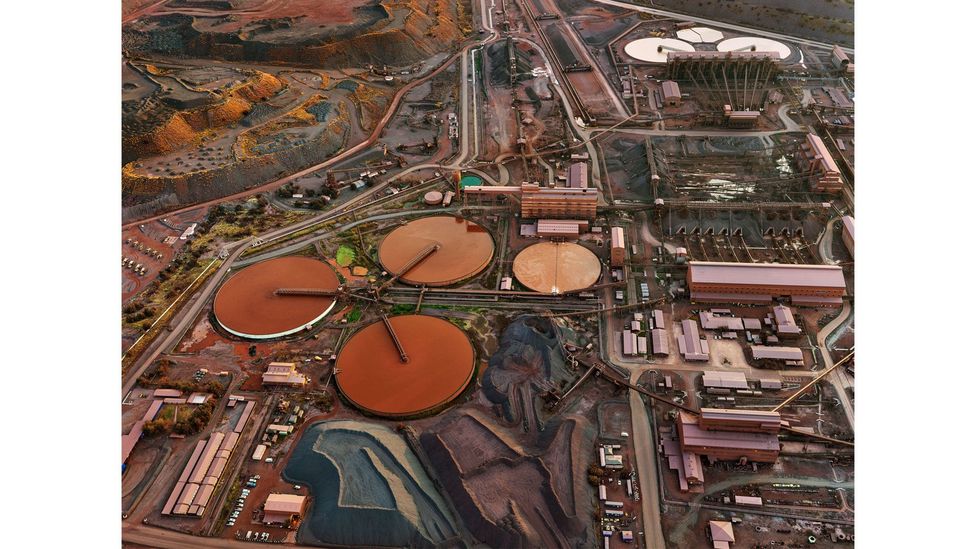

Sishen Iron Ore Mine #3, Kathu, South Africa, 2018 (Credit: Edward Burtynsky, Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto / Flowers Gallery, London)

GV: Your pictures are very painterly – do you see yourself more as an artist or more as a photojournalist?

EB: I kind of walk that line. What I share with photojournalism is that there’s a narrative behind it. There’s a story behind it. I would say that I lead with the art but everything that I’m photographing is linked to this idea of what we humans are doing to transform the planet. So that’s the overarching narrative, whether it’s wastelands or waste dumps, mines or quarries.

Sand Dunes #1, Sossusvlei, Namib Desert, Namibia, 2018 (Credit: Edward Burtynsky, Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto / Flowers Gallery, London)

GV: You do also photograph some natural landscapes, there is this kind of recurring pattern that quite often what you photograph almost looks natural because it has those natural patterns in it like repeating circles from agricultural monocultures or irrigation patterns or the extraction patterns in quarries and delta sludge, all of that, it also has those repeaters in nature that occur in plants and in natural river systems. I really liked your landscapes from Namibia, these natural sandscapes with the ancient sculpting of the bone-dry landscape.

EB: I’m leading with art, so I’m looking at art historical references, whether it’s abstract expressionism or other shared ideas with painting. I’ll look at a particular subject, then spend time on how to approach it. What am I going to link it into so that it appears in a way that has a signature of the work that I’ve been doing over time, and also shares in art history? If abstract expressionism never occurred as a movement, I don’t think I would make these pictures.

Desert Spirals #1, Verneukpan, Northern Cape, South Africa, 2018 (Credit: Edward Burtynsky, Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto / Flowers Gallery, London)

GV: It’s almost a translation, you’re seeing these system changes and you’re describing it to people in their language, in a familiar language that they already understand from the culture that they know – different artistic movements.

EB: To me, it’s interesting to say, ‘I’m going to use photography, but I’m going to pull a page out of that moment in history’. And if you look at it, throughout my work I’m pulling pages out of moments in history and saying, ‘Oh, this is the 18th-Century direct, beautifully composed approach – a deadpan approach to photographing – for instance, the pyramids. I’m going to use that, because the shipbreaking yards in Bangladesh call for this approach.’

Salt Ponds #4, near Naglou Sam Sam, Senegal, 2019 (Credit: Edward Burtynsky, Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto / Flowers Gallery, London)

GV: I just wanted to talk to you about the idea – something that you’re getting at with your images – this idea that we are living now in this human-changed world but nevertheless we are of course dependent on the Earth for everything and we’re all interconnected. I wonder how far a photograph can go to explaining that extremely complicated 3D concept of interconnectedness?

EB: One of the things that photography and documentary filmmaking can do is reveal these things again and again. It can show them, go to places where average people would normally not go, and have no reason to go, like a big open-pit mine. It can take you to the areas that we’re all dependent on, oil fields and copper mines and cobalt mines. I think it’s more compelling that way. People can absorb information better than reading – images are really useful as a kind of inflection point for a deeper conversation. I don’t think they can provide answers, but they can certainly lead us to awareness, and the raising of consciousness is the beginning of change.

With my photography, I’m coming in to observe, and my work has never been about the individual, it’s been about our collective impact, how we collectively rearrange the planet, whether building cities or infrastructure or dams or mines.

African Studies is now collected in a book and is on display at Flowers Gallery, Hong Kong until 20 May 2023.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

;