For more than 50 years, America’s official position on marijuana has been seen as nonsensical. By classifying pot as a Schedule I drug, the federal government has lumped it with heroin and LSD as substances with “no currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse.” In 1972, two years after marijuana was relegated to the most restrictive category of drugs in America, a government report found that weed’s “actual impact on society does not justify a social policy designed to seek out and firmly punish those who use it.”

Even with the federal classification, states have been experimenting with marijuana legalization for nearly three decades. These laws have led to fewer marijuana-related arrests without dramatic increases in crime, and they haven’t substantially spiked the rate of illicit adolescent cannabis use. Although fully legalizing recreational marijuana remains controversial, it’s clear that smoking a joint from your local dispensary is not the same as using heroin.

Now America’s marijuana policies are getting a bit more in line with the actual science. Today, Donald Trump signed an executive order directing the government to move the drug to Schedule III, a classification for substances with “moderate to low potential for physical and psychological dependence.” As the president emphasized in the Oval Office, the action “doesn’t legalize marijuana in any way, shape, or form.” Selling marijuana without a prescription will still be a federal crime, just as trafficking anabolic steroids (also a Schedule III drug) is illegal.

The biggest impact from today’s action will likely be on medical research. Marijuana studies have been stymied because researchers who want to experiment with Schedule I drugs need to be closely vetted by the federal government. During the signing ceremony for the executive order, Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. argued that the new classification will let scientists better understand the drug. That’s the hope of Ryan Vandrey, a cannabis researcher at Johns Hopkins University. Vandrey’s lab was cleared to do cannabis research while marijuana was still in Schedule I, but he hopes that this loosening of restrictions will open up “a huge number of possibilities for us to get at both the health benefits and health risks of cannabis as a whole,” he told me.

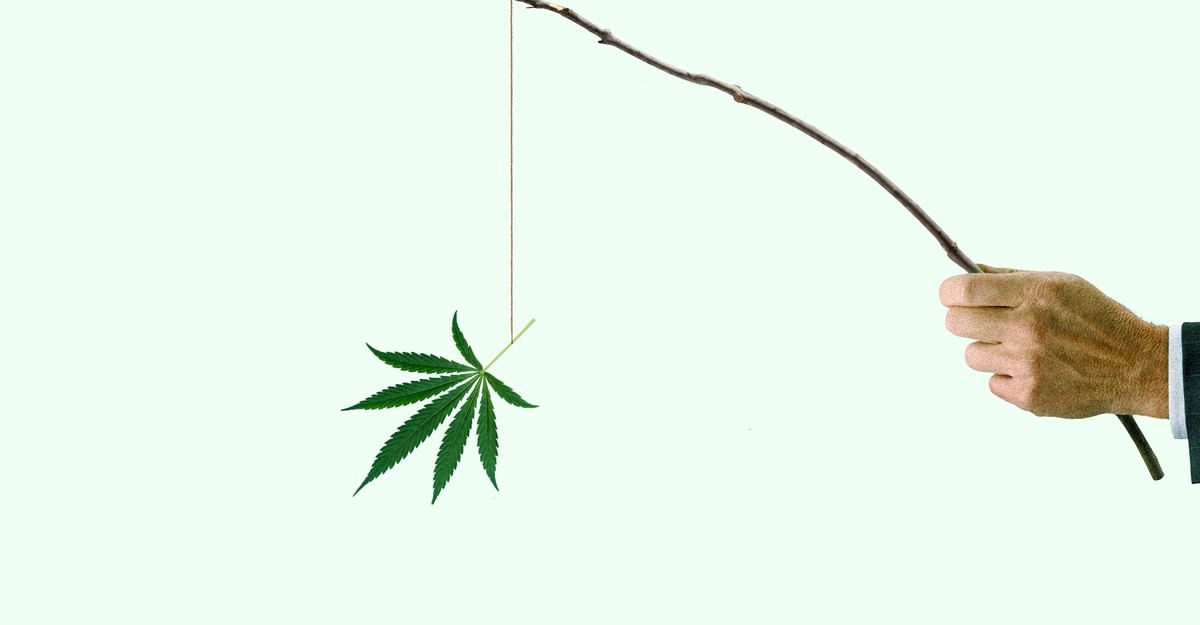

At the same time, by rescheduling the drug, the government runs the risk of signaling that marijuana is no big deal. “We need to be very clear in our messaging—especially to young people—that rescheduling does not mean cannabis is harmless,” Scott Hadland, a professor at Harvard Medical School and a pediatrician who treats adolescent addiction, told me. The government needs to figure out a way to tell Americans that even though marijuana is not as dangerous as heroin, it’s still an addictive drug. That’s not an easy message to communicate. Prior to signing the executive order today, the president touted the purported benefits of marijuana for certain medical conditions, but he also echoed the “Just Say No” drug campaign of decades past. “Unless a drug is recommended by a doctor for medical reasons, just don’t do it,” he said. (The White House did not respond to a request for comment.)

When talking about the risks of marijuana, you can easily to come off as a scold. Roughly 50 percent of Americans have tried the drug, and according to a 2024 study, the number of people using cannabis daily or near daily now eclipses the number who drink alcohol at a similar frequency. (Trump emphasized today that weed rescheduling polls well.) Even so, the risks of marijuana are real. The CDC estimates that three in 10 cannabis users exhibit some signs of dependency.

It doesn’t help that marijuana isn’t the same as when it was first scheduled, back in 1970. The drug has become significantly stronger over the past several decades. The average joint in the ’70s contained about 2 percent THC, the main psychoactive component of marijuana. In 2025, dispensaries regularly stock joints that have more than 35 percent THC. Studies have shown that use of higher-concentration marijuana is associated with serious mental-health outcomes, such as psychosis. In 2017, there were more than 100,000 hospitalizations for pot-linked psychosis, one study found. Vandrey said that he hopes rescheduling will help researchers better interrogate the “very strong correlation” between heavy marijuana use and psychosis.

None of this is to say that marijuana should stay a Schedule I drug, as it has for decades. In spite of this classification, millions of Americans have continued to use it. The government is now finally backing away from a misguided position about the risks of pot. But it still has to contend with the drug’s complications.